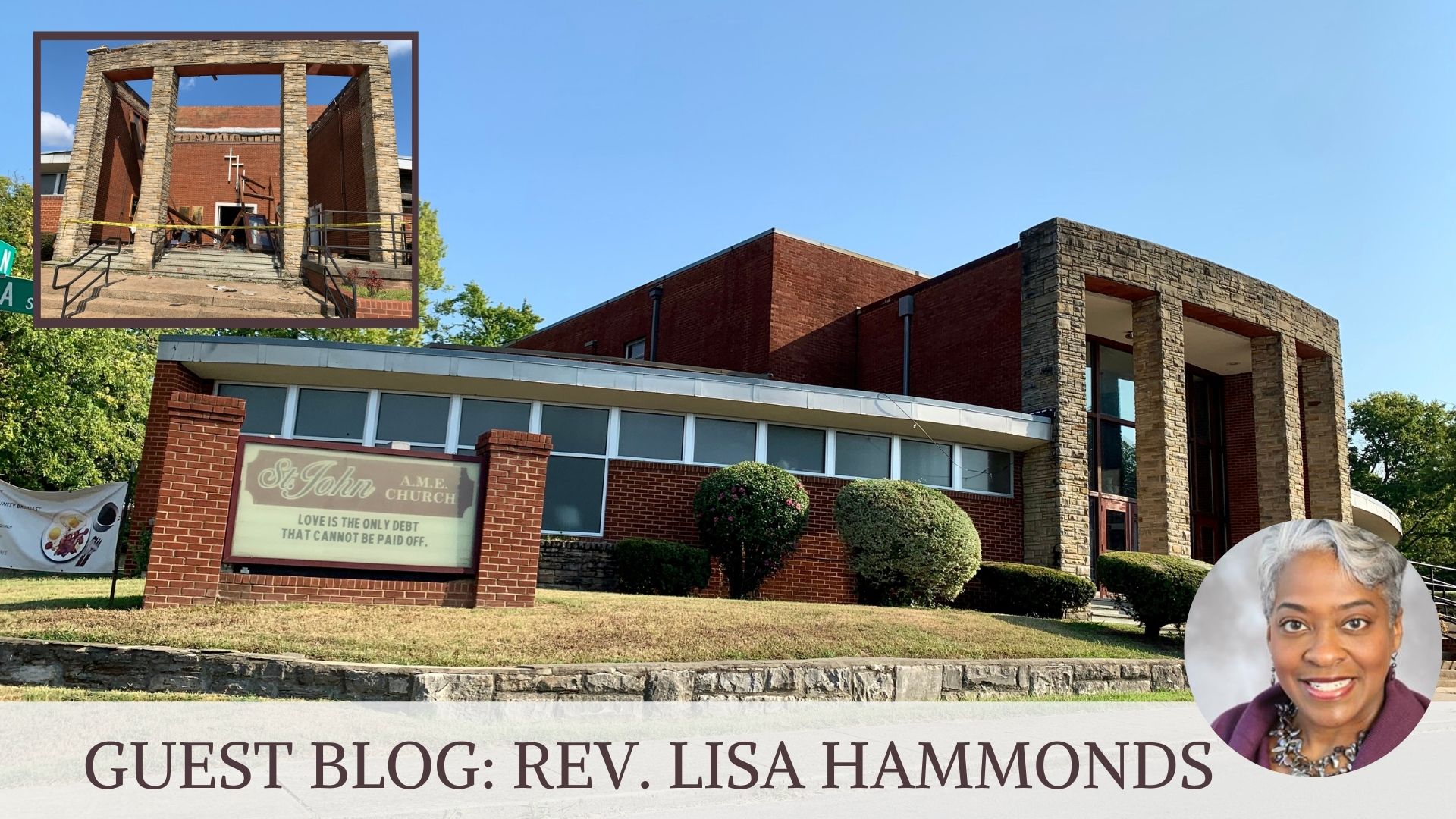

Editors Note: We are grateful to Rev. Lisa Hammonds, pastor of St. John AME Church, North Nashville, for sharing this two-part story of leading her congregation through tornado recovery. Read about the night of March 3 in How to Survive a Tornado – Part I here. To support the church in its recovery, you can send a donation on Cash App ($StJohnAMENashville).

How to Survive a Tornado ~ Part II

The rest of the week was a blur of volunteers that flooded into the area from near and far. All seemed excited to assist though some seemed to not understand my polite decline when they wanted to enter the building. I was waiting for the insurance adjuster who did not arrive until the end of the week.

The local media finally showed up, days after giving much attention to Germantown and Mt. Juliet, and after I gave interviews to the national press. There were lots of phone calls from colleagues, friends, family, and others offering space for worship, prayers, well wishes, and financial and physical support.

I also fielded many unsolicited calls and visits from people offering property adjusting services, roof repair, and financial lending. There were also predator property investors who were around, going door-to-door with offers to purchase damaged homes, even using drones to identify possibilities for further gentrification.

All Things Disaster Recovery

The following week was a crash course in all things disaster recovery. In order to access federal relief through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), it is necessary to first go through Tennessee Emergency Management Agency (TEMA) because the federal government does not deliver funds to individuals or businesses and any funds are disbursed to states.

After registering with TEMA, applicants are referred to the Small Business Administration (SBA) for consideration of a low-interest loan, which also influences FEMA’s response. None of the databases seem to speak to each other so navigating endless paperwork, follow up, and meeting deadlines are crucial.

Financial assistance is only possible after insurance is settled, and that entailed meetings with the insurance adjusters, building inspectors, structural engineers, appraisers, and content adjusters. Additional storms in Chattanooga and Mississippi slowed the whole process down. Within ten days, “safer-at-home protocols” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic began further delaying the process.

Financial assistance is only possible after insurance is settled, and that entailed meetings with the insurance adjusters, building inspectors, structural engineers, appraisers, and content adjusters. Additional storms in Chattanooga and Mississippi slowed the whole process down. Within ten days, “safer-at-home protocols” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic began further delaying the process.

We determined to worship on the second Sunday after the tornado in the chapel of a nearby funeral home. I set up an altar that included a St. John brick—more than 150 years old—salvaged from the former building and used in erecting the Formosa Street location. It illustrated the strength to withstand the hands of time gone by with its physical storms and us. The building might have been destroyed; but we, the members, are the church, and we remain.

The African Methodist Episcopal Church comes to Tennessee

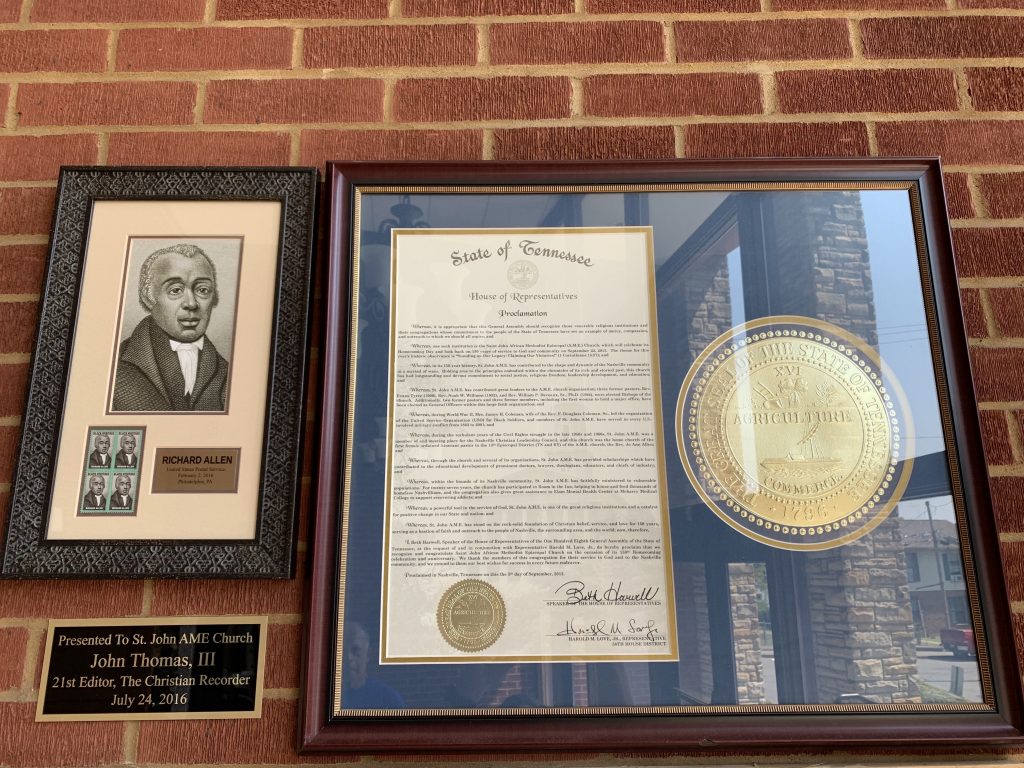

In 1787, despite its moniker as the City of Brotherly Love, relations between Whites and Blacks in Philadelphia were hostile. The church was no different. Black church structures did not exist. Thus, many Blacks attended White churches who opened their doors to them. Richard Allen and others were among Blacks who attended St. George’s Methodist Church.

Due to their growing numbers, Black worshippers were eventually pulled from their knees during prayer at a worship service. Repelled by this act of racial discrimination, Allen and others walked out of St. George’s. Allen and Absalom Jones formed the Free African Society on April 12, 1787, a mutual aid society, whose mission later became that of African Methodist Episcopal Church. Among their purpose was “to seek out and save the lost, and serve the needy.” Allen eventually purchased a plot of land and a blacksmith shop and reconstructed a church on the site. It was dedicated on July 29, 1794, as Bethel. Allen formally incorporated Bethel and other Black churches into the AME Church denomination in 1816.

Allen eventually purchased a plot of land and a blacksmith shop and reconstructed a church on the site. It was dedicated on July 29, 1794, as Bethel. Allen formally incorporated Bethel and other Black churches into the AME Church denomination in 1816.

+++++++++

Forty-seven years after that historic exodus, the Civil War embroiled and split the United States. The AME Church began expansion which included sending a bishop to Tennessee. On December 5, 1863, Bishop Daniel Payne arrived in Nashville with letters of introduction from the Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Treasury that he presented to Governor Andrew Johnson, who granted Bishop Payne permission to organize AME Churches in Tennessee.

This timing coincided with dissatisfaction among some members of the Capers Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church. Capers was the first Negro meeting house in Nashville. This group of disenchanted members, led by Napoleon Merry—a 39-year old free Black—made application to become part of the AME Church. Bishop Payne accepted the application.

Thus, St. John AME Church was born with the Rev. Merry as the first pastor. The first house of worship was at the present corner of Rosa Parks Boulevard and Gay Street.

Twentieth Century Displacement and Gentrification

In 1956, St. John was one of six black faith communions located in the North Capitol area of Nashville. Home to the most coveted view of the state capitol, the Capitol Hill Redevelopment Program, a post-war urban development initiative, displaced five of these black churches and their church communities, privileging the installation of the James Robertson Parkway. Looping around the bottom of the Capitol building and up to 8th Avenue, this construction effectively decimated the presence of African American churches in the area by acquiring all of the property through Eminent Domain.

Without prior discussion or negotiation, the Capitol Hill Redevelopment Program announced their plans to St. John (1863), Gay Street Christian Church (1859), Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church (1887), St. Andrews Presbyterian Church (1898), and Spruce Street Baptist Church (1848). First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill—the sixth black church in the vicinity—was spared.

St. John AME’s current location at 1822 Formosa Street in North Nashville, was erected with salvaged bricks and stained glass from the original 1863 edifice.

Post-displacement, two years passed before St. John rebuilt at 1822 Formosa Street in North Nashville—one block away from the historic Jefferson Street, the bustling black business district. Following the Nashville Sit-ins in the early 1960s—as if in retaliation—the construction of I-40 destroyed much of North Nashville’s thriving neighborhood, particularly its historic Jefferson Street corridor, with its famous music venues, retail establishments, and restaurants. St. John’s newly-erected Formosa Street location, together with Capers Memorial CME Church, and Lee Chapel AME Church narrowly avoided further disruption.

++++++++

Since its founding, 42 pastors furthered the spiritual refuge, socio-economic support, social justice, and pride in the community of St. John. I am its first female pastor, a daughter of the historic congregation. I was raised, baptized, and formally acknowledged ministry. The Bishop appointed me as pastor of St. John in 2018.

St. John, “The Mother Church of African Methodism in the state of Tennessee,” will continue to be a bulwark for the community. Its worship, benevolence, and ministries including Meals on Wheels and Room in the Inn will continue through the people who make up the church.

Deconsecration

Three and a half months after the storm, on June 26, St. John held a Deconsecration Service, removing the sacredness of the building prior to its impending demolition. The presiding prelate, Bishop Jeffrey Nathaniel Leath, of the Thirteenth District of the AME Church and Nashville’s mayor, John Cooper both attended and participated as did former pastors.

Two weeks later, the building was demolished and the debris removed. We reserved a sampling of the bricks as well as the remaining stained-glass windows. Soon seed and hay will cover the property.

The church is currently engaging in a season of fasting and praying for discernment, wisdom, and direction for the next steps. We are seeking a spirit of unity and cooperation and favor. I’m also securing the help of a consultant that will guide us in the process of planning, evaluating, and proceeding.

The church is currently engaging in a season of fasting and praying for discernment, wisdom, and direction for the next steps. We are seeking a spirit of unity and cooperation and favor. I’m also securing the help of a consultant that will guide us in the process of planning, evaluating, and proceeding.

At the insistence of some of my church leadership and family members, I took some time off. It is nearly impossible to totally disconnect as a pastor. Even at times this summer while I was “away,” there were deaths in my family, at church, and with a student-mentee. Alas, time to refresh is necessary.